Echoes of the Past

A Journey Through Asian American History

You are Chen Wei, a young man from Guangdong Province, China. The year is 1912, and you have saved every coin to buy passage to America- the "Gold Mountain" where streets are said to be paved with opportunity.

Your village has been devastated by floods and foreign wars. Your family depends on you to find work and send money home. But America passed the Chinese Exclusion Act thirty years ago, and the new Angel Island Immigration Station has made the journey more perilous than ever.

As your ship approaches San Francisco Bay, you can see Angel Island in the distance. Your heart pounds with both hope and fear.

The Wooden Prison

You are herded off the ship with dozens of other Chinese immigrants. The building before you looks more like a prison than a gateway to opportunity.

With barbwire surrounding us.

We are like birds in a cage here,

Not knowing when we will be deported."

An immigration inspector approaches with a thick folder of papers. His eyes are cold, calculating. "Name?" he barks.

You clutch your forged documents tighter. Your real name is Chen Wei, but your papers say "Chen Bo"- claiming you're the son of a merchant already in America, which would give you the right to enter.

Echoes That Remain

[You are now playing as yourself, someone studying this history]

You have completed your journey through the echoes of the past. From Chen Wei's arrival at Angel Island to Kenji's imprisonment and eventual rebuilding, you have experienced the complex choices faced by Asian Americans throughout history.

The decisions you made- whether to tell the truth or lie, to resist or comply, to assimilate or preserve culture- mirror the impossible choices forced upon generations of Asian Americans by systemic oppression and exclusion.

Today, Asian Americans still face questions of belonging, representation, and identity. The echoes of exclusion still reverberate in immigration debates, hate crimes, and the perpetual foreigner stereotype.

But the echoes of resistance, resilience, and community also continue. Each generation builds upon the sacrifices and courage of those who came before.

Your Final Choice

How will you use this understanding of the past to shape the future?

The Weight of Truth

"My name is Chen Wei," you say, your voice barely above a whisper. "I am a laborer from Guangdong Province."

The inspector's face hardens. "Laborer?" He stamps a red mark on your file. "Chinese laborers are prohibited entry under the Exclusion Act of 1882."

Not knowing when we will be deported."

You are taken to the detention barracks. The walls are covered with poems carved by previous detainees- expressions of hope, despair, and defiance.

Three months pass. Every day brings interrogations, the same questions over and over. Some men have been here for over a year. Others have given up and accepted deportation.

The Lie That Might Save You

"Chen Bo," you reply, showing your forged documents. "Son of Chen Ming, merchant in San Francisco Chinatown."

The inspector studies your papers carefully. For weeks, you are held while they verify your story. You memorize every detail of the fake family history- ages, addresses, the layout of a house you've never seen.

Finally, you face the interrogation board. They ask about your supposed father's business, your childhood memories, the number of steps to your house in China.

Carved in Wood, Carved in Memory

With a broken nail and fierce determination, you begin carving your own poem into the wooden wall:

"Ten thousand li from home,

Separated by an ocean of tears.

Golden Mountain calls to me,

But iron bars hold me here.

I did not come to steal or harm,

Only to work and send home gold.

Why must my skin make me enemy

In a land that claims to welcome all?"

Your poem joins hundreds of others- a testament to the dreams and struggles of those who came before you.

Freedom, But at What Cost?

Your careful preparation pays off. After six months of detention, you are finally admitted to America. You step off the ferry at San Francisco with nothing but the clothes on your back and the weight of a lie that will follow you forever.

San Francisco's Chinatown is crowded, loud, and alive with opportunity and desperation in equal measure. You find work in a laundry, sending most of your earnings back to your family in China.

Years pass. You build a life, but you can never shake the fear that your true identity will be discovered. You carry forged papers everywhere, knowing that at any moment, you could be questioned and deported.

Living Under Suspicion

Ten years have passed since you arrived. The Chinese Exclusion Act has been renewed multiple times, and life for Chinese Americans grows more difficult each year. You now own a small shop in Chinatown, but prosperity brings new dangers.

A group of white merchants approaches your shop. They demand you pay "protection fees" and threaten to report you to immigration authorities if you refuse. You know other Chinese businesses that have been destroyed by such threats.

You also know about the Chinese community organizations that help protect their members, but joining them means acknowledging your false identity to people who might expose you.

Strength in Unity

You decide to trust your community. You approach the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, knowing you must reveal your true story to gain their protection.

To your surprise, the association leaders are understanding. Many others have similar stories. They help you obtain proper documentation and provide legal support when the white merchants try to follow through on their threats.

But your courage comes at a cost. Word spreads that you stood up to the protection racket, and you become a target for both white supremacists and other criminals.

You have also caught the attention of a young teacher named Mary, who works with Chinese immigrant children. She admires your courage and you find yourself falling in love- but mixed-race relationships face severe social and legal barriers.

The Fight for Justice

You dedicate yourself to fighting for the rights of Chinese Americans. You help organize legal challenges to discriminatory laws and work with lawyers fighting the exclusion acts.

Your case becomes part of a larger movement. You witness the historic Wong Kim Ark case, which establishes that children born in America to Chinese parents are citizens regardless of their parents' status.

Your activism brings both victories and new dangers. You help dozens of immigrants navigate the legal system, but you also face constant threats and surveillance.

Seeds of the Future

You realize that true change will come through the next generation. You establish a school for Chinese American children, teaching them both English and Chinese, American civics and Chinese culture.

Your students include children born in America who have never seen China, and recent immigrants still learning English. You teach them to be proud of both their heritage and their American identity.

One of your students is Kenji Nakamura, a bright Japanese American boy whose family runs a flower shop. You form a friendship with his family, bonding over shared experiences of discrimination and hope for the future.

But the world is changing. War clouds gather, and anti-Asian sentiment grows stronger.

The Journey Home

After months of detention, you accept deportation. The return voyage is bitter- you carry the knowledge that America's promise was not meant for people like you.

Back in China, you use the stories from Angel Island to warn others about the reality of American exclusion. Some listen; others still dream of Gold Mountain.

You spend your life documenting the poems and stories from Angel Island, preserving the voices of those who suffered in the wooden barracks.

Your choice to return becomes a different kind of resistance- bearing witness to injustice and ensuring the stories survive.

The Price of Safety

You reluctantly pay the protection money, month after month. It eats into your savings and the money you send home to your family. Each payment feels like swallowing poison, but you tell yourself it's the price of staying in America.

Other Chinese businesses around you close down, unable to afford the escalating demands. You survive, but at what cost? The weight of compromise grows heavier each day.

Years pass. You build a modest life, always looking over your shoulder, always paying the price for peace. You learn that the great 1906 earthquake, which happened before you arrived, destroyed most of Chinatown's records, creating opportunities for some immigrants to claim American birth.

Fighting the System

You refuse to give up. With the help of other detainees, you learn about habeas corpus petitions and legal challenges to detention. Some Chinese community organizations in San Francisco are fighting immigration cases in court.

A letter arrives from a lawyer willing to take your case. The legal fees will consume all your savings and more, but it's your only hope.

Months pass. Court appearances, legal briefs, appeals. You watch some win their cases and walk free, while others lose and face deportation.

Justice, At Last

Against all odds, the court rules in your favor. A technicality in your detention process grants you entry to America. You walk free, but the legal battle has left you penniless and emotionally drained.

In Chinatown, you're welcomed as a hero- one of the few who beat the system legally. Community leaders ask you to help others navigate the legal system.

You realize your victory comes with responsibility: to help others who face the same impossible situation you escaped.

When History Repeats

[You are now playing as Kenji Nakamura, the former student of Chen Wei, now grown with a family of your own]

You are Kenji Nakamura, 35 years old, owner of a flower shop in San Francisco. Your wife Michiko and your two young children, David and Susan, have built a good life in America. You were born here, your children were born here, yet everything is about to change.

December 7, 1941. Pearl Harbor.

Within weeks, Executive Order 9066 is signed. All persons of Japanese ancestry on the West Coast must report for "evacuation."

Your old teacher Chen Wei, now in his 60s, comes to your shop with tears in his eyes. "This is what I feared," he says. "They did it to us with the exclusion acts, now they do it to you with camps. When will America live up to its promises?"

The Horse Stalls

You decide compliance is the safest path for your family. You sell your flower shop for a fraction of its value to a white neighbor who promises to "take care of it" until you return.

You report to the Tanforan Assembly Center- a converted racetrack. Your family is assigned to a horse stall barely large enough for the four of you. The smell of manure still lingers despite the whitewash on the walls.

Your children ask why they can't go home, why they're living like animals. How do you explain injustice to a 6-year-old?

Making Beauty from Ashes

You are transferred to Manzanar in the California desert. Determined to maintain dignity and hope, you start a small garden using seeds smuggled in by your wife.

Your son David excels in the camp school, while Susan draws pictures of the mountains beyond the barbed wire. You tell them stories of their grandparents, keeping culture alive despite the circumstances.

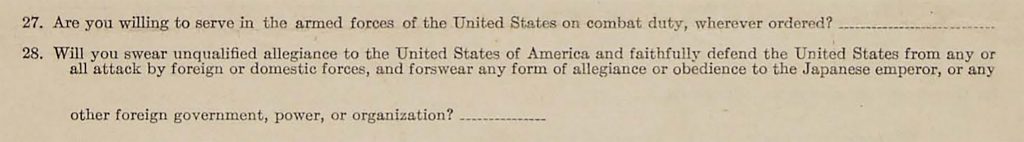

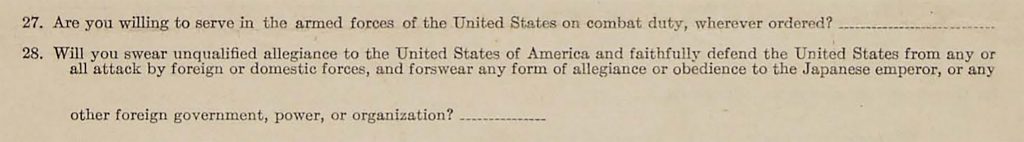

But the "loyalty questionnaire" arrives. Question 27 asks if you will serve in the U.S. military. Question 28 asks if you will "forswear any form of allegiance to the Japanese emperor."

The actual loyalty questionnaire questions that determined the fate of Japanese American families

Fighting for a Country That Imprisoned You

You volunteer for the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the segregated Japanese American unit. Your wife and children remain in Manzanar while you fight in Europe.

The 442nd becomes the most decorated unit in U.S. military history, proving loyalty through blood and sacrifice. You fight in France and Italy, wondering if your courage will be enough to earn acceptance for your people.

You are wounded in the rescue of the "Lost Battalion" in France. As you recover in a field hospital, you receive letters from Michiko describing life in the camp, your children growing up behind barbed wire.

The Bitter Homecoming

You return home with a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star, only to find your flower shop has been sold to someone else. Your neighbor claims you "abandoned" the property.

Your family is released from Manzanar, but where can you go? Anti-Japanese sentiment remains high. Your children struggle to readjust to life outside the camps.

Your old teacher Chen Wei, now 64, welcomes your family into his home. "We survived the exclusion," he says. "You survived the camps. Together, we will rebuild."

The Long Arc of Justice

Twenty years have passed. You and Chen Wei have worked tirelessly to rebuild not just your businesses, but your communities. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 finally repeals the Chinese Exclusion Acts.

Your children have grown up to become doctors, teachers, and activists. They carry forward the lessons of both your struggles and your resilience.

You attend the signing ceremony for the Hart-Celler Act, which ends decades of Asian exclusion. Chen Wei, now 83 years old, says with tears in his eyes: "I never thought I would live to see this day."

The Choice to Hide

You decide to resist the evacuation order. With help from Quaker friends and sympathetic neighbors, you attempt to hide your family in a basement safe house outside the exclusion zone.

For weeks, you live in constant fear. Every knock at the door could mean discovery. Your children cannot go outside, cannot attend school. The isolation weighs heavily on everyone.

Finally, the inevitable happens. FBI agents, acting on a tip, discover your hiding place. You are arrested and charged with violating the evacuation order- a federal crime.

The No-No Boys

You answer "No-No" to both questions on the loyalty questionnaire. It's not about loyalty- it's about principle. How can they ask for loyalty while denying you basic rights?

Your family is transferred to Tule Lake, the segregation center for "disloyals." Conditions here are harsher, with more guards, more rules, more suspicion.

You are labeled a troublemaker, but you find solidarity with others who chose principle over expedience. Together, you organize protests, write letters, and document the injustices you witness.

The Learning Continues

You have taken the first step in understanding a complex and often overlooked part of American history. This game only scratches the surface of the Asian American experience.

To continue your learning:

- Read "Kiyo's Story" by Kiyo Sato

- Watch "Rabbit in the Moon" documentary

- Visit the Angel Island Immigration Station

- Explore the Japanese American National Museum

- Study the Chinese Exclusion Act and its lasting impacts

Remember: History is not just about the past- it shapes our present and informs our future choices.

The echoes of the past are calling. How will you answer?

Thank you for playing "Echoes of the Past."

Play againBecoming a Bridge

By sharing these stories, you become part of the echo- carrying forward the voices of those who came before and ensuring their experiences are not forgotten.

Ways to share:

- Discuss this history with friends and family

- Include Asian American perspectives in educational settings

- Support Asian American authors, filmmakers, and artists

- Advocate for inclusive curriculum in schools

- Use social media to amplify marginalized voices

Remember: Every story shared is an act of resistance against erasure and a step toward a more complete understanding of American history.

The echoes of the past are calling. How will you answer?

Thank you for playing "Echoes of the Past."

Play againThe Past as Prologue

The themes you experienced- exclusion, detention, loyalty questioned, choices between resistance and compliance- are not relics of the past. They echo in current debates about immigration, citizenship, and belonging.

Current echoes include:

- Immigration detention and family separation

- Questions of loyalty and "un-American" activities

- Anti-Asian hate crimes and scapegoating

- The model minority myth and its limitations

- Ongoing struggles for representation and voice

The question remains: What choices will you make when faced with injustice? Will you speak up or stay silent? Will you seek safety or stand for principle?

The echoes of the past are calling. How will you answer?

Thank you for playing "Echoes of the Past."

Play againThe Truth Revealed

Under intense questioning, you crack and admit your papers are false. The inspector's face shows no surprise- they suspected all along.

You are marked for deportation, but the process takes months. During this time, you witness the daily struggle of other detainees and learn about the various ways people try to enter America.

Some have real family connections but lack proper documentation. Others, like you, have crafted elaborate false identities. All are trapped in the same wooden prison, waiting for justice that may never come.

Justice Denied

The court rules against you. Despite your lawyer's best efforts, the system is designed to exclude, not include. Your last hope is gone.

As you prepare for deportation, you meet other detainees who share their stories. You realize that your individual struggle is part of a larger pattern of exclusion.

You decide to document these stories, to ensure that the voices of those trapped on Angel Island are not forgotten.

Starting Over

You close your shop and move to Sacramento, hoping to escape the protection racket and start fresh. But discrimination follows you wherever you go.

In Sacramento, you face the same challenges: hostile neighbors, discriminatory laws, and the constant fear of deportation. You realize that the problem isn't your location- it's the system itself.

You begin corresponding with other Chinese communities up and down the coast, sharing information about legal challenges and organizing mutual aid.

From Ashes, New Identity

You learn that the great earthquake and fire of 1906 destroyed most of San Francisco's records, including immigration documents. Though it happened before you arrived, many Chinese immigrants have used this opportunity to claim American birth. You finally decide to do the same.

You file papers claiming you were born in San Francisco before the earthquake. Without records to contradict you, and with the help of community members who vouch for your "family history," the authorities accept your claim.

For the first time in ten years, you feel truly free. But your new freedom comes with responsibility- you use your status to help other Chinese immigrants navigate the legal system.

Fighting for Others

Your legal victory becomes a beacon of hope for other Chinese immigrants. You work with lawyers and community organizations to challenge unjust detentions and deportations.

The work is exhausting and often heartbreaking. For every case you win, dozens more are lost. But each victory proves that the system can be challenged, that justice is possible.

You document successful legal strategies and share them with Chinese communities across the country. Your experience becomes a template for resistance.

The Fire of Injustice

The anger burns inside you like acid. How can they do this to American citizens? How can they cage children behind barbed wire and call it protection?

Your anger spreads to others in the camp. You organize meetings, write letters of protest, and document the conditions. Some call you a troublemaker; others see you as a voice of conscience.

The camp administration labels you a "disloyal agitator." You're placed under closer surveillance, but your resistance inspires others to speak up.

The Will to Endure

You focus entirely on survival- keeping your family fed, healthy, and together. Politics and protests are luxuries you can't afford when your children's welfare is at stake.

You learn to navigate the camp's black market, trade favors for extra food, and keep your head down during roll calls. Your only goal is to emerge from this ordeal with your family intact.

When the loyalty questionnaire arrives, you face a critical decision that could determine your family's fate.

The actual loyalty questionnaire questions that determined the fate of Japanese American families

The Right to Remain Silent

You refuse to answer the loyalty questionnaire. "This is America," you tell the officials. "I have the right to remain silent when faced with unconstitutional questions."

Your refusal is treated as disloyalty. You're transferred to Tule Lake with the "No-No Boys" and others deemed security risks.

But your principled stand inspires others. Even in Tule Lake, you continue to assert your constitutional rights and demand justice.

Service Before Return

You decide to remain in Europe temporarily to help with reconstruction efforts. In France, you're seen as a liberator, a hero who helped free their country from fascism.

You work with Allied forces to help resettle displaced persons and rebuild communities destroyed by war. Your experience with discrimination and displacement makes you particularly effective at helping refugees.

For two years, you serve in post-war reconstruction, but your heart remains with your family in America. You write frequent letters home, explaining your temporary service and your plans to return.

In 1947, you finally return to America, bringing with you new perspectives on justice and human rights that will inform your continued activism.

Second Chances

You move your family to Chicago, where the Japanese American community is smaller but more accepted. The Midwest offers opportunities that the West Coast denies.

Your children adapt to their new environment, but they carry invisible scars from the camps. You enroll them in therapy- a revolutionary concept at the time- and slowly, your family begins to heal.

You open a small nursery, growing flowers again. Each bloom feels like an act of defiance against those who tried to destroy your spirit.

The Long Road to Healing

You dedicate yourself to helping your family heal from the trauma of incarceration. Your children struggle with nightmares, anxiety, and questions about their identity as Americans.

You create a safe space for them to express their anger, confusion, and pain. You also connect with other families dealing with similar struggles, forming support networks that didn't exist before.

Your nursery becomes more than a business- it becomes a gathering place for Japanese American families rebuilding their lives. You teach children gardening as a way to heal and connect with beauty.

Years pass. Your children grow strong, becoming doctors, teachers, and artists. They carry forward both the pain and the resilience of their experiences.

Supporting the Movement

From your new home in Chicago, you quietly support civil rights organizations and Japanese American advocacy groups. You send money, write letters, and share your story when asked.

You see parallels between your incarceration and the treatment of African Americans in the South. When the Montgomery Bus Boycott begins, you organize fundraising efforts in the Japanese American community.

Your business thrives, allowing you to financially support multiple civil rights causes. You become a bridge between Asian American and African American communities in Chicago.

When the Immigration and Nationality Act passes in 1965, you celebrate with Chen Wei via telephone. Two old friends, having survived exclusion and incarceration, witness the legal dismantling of anti-Asian discrimination.

Resistance Behind Barbed Wire

You organize hunger strikes, petition drives, and peaceful protests within the camp. Your actions inspire others, but they also bring harsh crackdowns from the administration.

Soldiers patrol the camp with loaded weapons. Your children ask why the American flag flies over what feels like a prison.

Despite the risks, you continue to document the injustices you witness, smuggling letters to the outside world through sympathetic guards and visitors.

The Decades-Long Struggle

You spend decades fighting discriminatory laws through the courts. Your hair turns gray, your eyes grow tired, but your determination never wavers. Each small victory builds toward eventual justice.

When Executive Order 9066 is signed in 1942, you're ready. Your experience fighting Chinese exclusion laws provides a blueprint for challenging Japanese American incarceration.

You work with civil rights lawyers to file constitutional challenges. Many cases are lost, but each one creates legal precedent and keeps the flame of justice alive.

Your most important victory comes in 1965 when the Immigration and Nationality Act finally repeals the Chinese Exclusion Act. You're 83 years old, but you live to see the legal framework of Asian exclusion dismantled.

Love Across Barriers

You and Mary face enormous social pressure, but your love transcends racial boundaries. Together, you work to educate children and build bridges between communities.

Flight to Freedom

You attempt to escape the exclusion zone by moving inland, but the authorities catch up with you. Your flight becomes evidence of "disloyalty" in their eyes.

A Quiet Life

You choose to live quietly, avoiding attention. For fifteen years, you pay the protection money and keep your head down. Your business survives, though you never prosper.

By 1930, you've saved enough to bring your brother's son from China to help in the shop. The young man, Li Wei, arrives full of hope and energy- reminding you of yourself decades ago.

You take him under your wing, teaching him not just the business, but how to navigate America's complex racial landscape. Through mentoring him, you find new purpose.

As the years pass, you watch the Chinese American community grow and change. Second-generation children attend American schools, and some even go to university. The future looks brighter than the past.

The Elder's Wisdom

At 53, you've become a respected elder in Chinatown. Young people seek your advice, and you serve on the board of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association.

You've lived through the exclusion era, witnessed the community rebuild after the 1906 earthquake that happened before your arrival, and seen tremendous changes. But new challenges arise as anti-Asian sentiment grows again with tensions in Asia.

One of the young men you've mentored is Kenji Nakamura's father- a Japanese immigrant who faces his own discrimination. You form an unlikely alliance across ethnic lines, understanding that all Asian Americans face similar struggles.

When war comes to the Pacific in 1941, you know the pattern will repeat itself. The question is: what can you do to help?

Rebuilding from Nothing

You focus on rebuilding your own life first, knowing that you must be strong before you can help others. It takes years to establish yourself again, but slowly you build a small import business.

You benefit from the opportunities created when the 1906 earthquake destroyed many city records. Though it happened before your arrival, this historical event allowed many Chinese immigrants to claim American birth, and you eventually do the same to gain legal security.

Your business grows, and by 1925, you employ several other Chinese immigrants. You remember what it was like to struggle alone, so you provide not just jobs but guidance and community support.

As your hair turns gray, you realize that your quiet survival has become a form of leadership. The younger generation looks to you as an example of perseverance.

Community Connections

You help build a network of Chinese communities up and down the California coast, sharing resources and legal strategies. Your correspondence network becomes a lifeline for isolated immigrants.

You learn from older immigrants about how networks sprang into action after the 1906 earthquake, when communities from Sacramento to Los Angeles sent aid to San Francisco. Now you're building on those lessons, creating even stronger bonds between Chinese Americans.

Your network proves crucial in navigating ongoing discrimination. Information flows quickly about legal opportunities, business openings, and ways to help newcomers establish themselves legally.

By 1930, your network has evolved into one of the first statewide Chinese American organizations. You've helped establish schools, temples, and mutual aid societies across California.

The Eternal Wanderer

You continue moving from place to place- Sacramento, Stockton, even as far as Chicago- searching for acceptance that seems always just out of reach. Each move brings new challenges but also new perspectives.

In your travels, you meet Chinese immigrants in small towns, isolated and struggling. You begin documenting their stories, creating an informal history of Chinese American experiences outside the major cities.

Your wandering becomes purposeful research. You collect stories, legal documents, and testimonies that paint a picture of Chinese American life across the nation.

By 1935, you've compiled one of the most comprehensive records of Chinese American experiences during the exclusion era. Scholars and activists seek out your documentation.

Keeper of Memory

Your documentation work has made you an unofficial historian of the Chinese American experience. Universities invite you to speak, and journalists interview you about the exclusion era.

As tensions rise in Asia and anti-Asian sentiment grows again, your historical perspective becomes valuable. You can see patterns repeating- the same scapegoating, the same fears, the same injustices.

When Executive Order 9066 is signed in 1942, you're not surprised. You've seen this before with Chinese exclusion. You reach out to Japanese American communities, offering your documentation of resistance strategies.

Your lifetime of recording injustice becomes a resource for those facing new persecution. History doesn't repeat exactly, but it does echo.

The Sacrifice of Love

You leave San Francisco to protect both yourself and Mary from social persecution. The pain of lost love is sharp, but you carry with you the knowledge that your feelings were real and mutual.

You settle in Oregon, where the Chinese community is smaller but faces different challenges. Your experience in San Francisco's activism makes you a natural leader here.

Over the years, you correspond secretly with Mary. She continues her teaching work, and you organize mutual aid societies. Your love, though forced apart, inspires both of you to fight for justice.

By 1930, you've helped establish one of the first integrated schools in Oregon. Your sacrifice for love has transformed into a broader fight for acceptance and equality.

Love's Long Echo

A letter arrives from Mary after nearly thirty years. Her husband has died, and she's retiring from teaching. She writes: "I never stopped thinking about you, or the work we could have done together."

You're both older now, gray-haired and weathered by decades of separate struggles. But when you meet again, the connection is still there- deeper now, enriched by years of shared purpose if not shared presence.

Together, you establish a foundation to support Asian American students. Your love story becomes a partnership that bridges racial lines and generations.

As you age together, you often discuss how personal choices intersect with historical forces. Your love survived by transforming into something larger than yourselves.

Constitutional Challenge

You fight the charges in court, arguing that Executive Order 9066 violates the Constitution. Your case becomes part of the historical record of resistance.

Protecting Family

You accept a plea bargain to protect your family from harsher punishment. Sometimes love means accepting injustice to shield those you care about.

Refusing to Renounce

The pressure to renounce American citizenship has become overwhelming at Tule Lake. Camp officials present it as an opportunity: "If you renounce, you can be repatriated to Japan after the war. Your troubles in America will be over."

Over 5,000 Japanese Americans will eventually renounce their citizenship - some in protest, others under duress, many believing they have no future in America. The renunciation program becomes a weapon used against people who have already lost everything.

You refuse. "I am an American citizen," you tell the officials. "That's not something you can take away, and it's not something I will give up. My children were born here. This is our home."

Your refusal marks you as a troublemaker. You're moved to the most secure section of Tule Lake, where conditions are harsher and surveillance is constant. But you're not alone - others have also chosen to endure rather than renounce.

Camp guards whisper that the war is turning. Germany has surrendered. Japan is losing. The camps may close soon. Your decision to hold onto your citizenship, despite everything, may prove wise - but the immediate cost is high.

Defiance Under Watch

In the high-security section of Tule Lake, you find others who refused to renounce their citizenship. Together, you form a core of resistance within the resistance - people who will not be broken by any pressure.

Despite constant surveillance, you continue organizing. You develop new communication methods: messages hidden in laundry, signals using hanging clothing, coded conversations during meal times. The authorities increase security, but they cannot stop determined people from connecting.

You organize a hunger strike to protest the renunciation program. Dozens join you, refusing meals until the pressure tactics stop. The camp administration brings in doctors who warn of health consequences, but you persist.

After eight days, national media attention forces improvements in camp conditions and the end of the most coercive renunciation tactics. Your resistance has protected others from the worst pressures.

Standing with Families

You focus your energy on supporting other families facing the impossible choice about renunciation. In the barracks at night, you hold quiet meetings where people can discuss their fears and options without judgment.

Mrs. Tanaka breaks down crying: "My husband wants to renounce so we can all go to Japan together. But my children have never left California. How can I take them to a country they don't know?" You hold her hands and listen, offering no easy answers because there are none.

You help establish a support network for families, regardless of their decision. Those who renounce need help preparing for repatriation. Those who don't need help resisting pressure. Both need to know they're not alone.

Your work helps dozens of families navigate this crisis. Some choose renunciation, others refuse, but all know they had support and understanding during their darkest hour.

Years later, many will tell you that your compassion during the renunciation crisis helped them maintain their humanity when the system tried to destroy it.

Bearing Witness

You document every injustice, every violation of rights. Your records become crucial evidence for future reparations and historical truth.

Building the Network

You begin by identifying trustworthy people across multiple camps. A former newspaperman at Manzanar becomes your information coordinator. A teacher at Topaz organizes coded lesson plans that carry messages. A mechanic at Poston repairs "broken" radios that somehow pick up outside frequencies.

The network grows carefully, slowly. Each new member is vetted through multiple contacts. You develop a system using innocuous family letters, with specific phrases that convey urgent information: "Uncle Taro's harvest was poor" means guards are searching barracks. "Grandmother's tea is getting cold" means a lawyer is coming to visit.

Within six months, your network spans eight camps and reaches sympathetic contacts in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Chicago. Information flows both ways-- news from the outside world reaches the camps, while documentation of abuses flows outward to civil rights organizations and sympathetic journalists.

But expansion brings risk. Camp administrators are beginning to notice patterns in the mail. Some guards are asking questions about seemingly innocent conversations. You must decide how to proceed.

Expanding the Web

You decide the cause is worth the risk. Working with your most trusted contacts, you expand the network to include sympathetic guards, local townspeople near the camps, and even some camp administrators who privately oppose the incarceration.

A Quaker relief worker becomes a crucial ally, carrying messages between camps during her official visits. She later writes: "These people were doing more than surviving-- they were maintaining their humanity and their resistance in the face of dehumanization."

The network grows to include 200 active participants across ten camps. You coordinate resistance activities: hunger strikes happen simultaneously across multiple facilities, legal challenges share information and strategies, and documentation efforts create a comprehensive record of injustices.

By 1944, your network has become instrumental in organizing the "leave clearance" protests and supporting those who refuse to sign loyalty questionnaires. Your underground communication system proves that walls and barbed wire cannot contain the human spirit.

Protecting the Network

Recognizing that exposure could mean punishment for hundreds of people, you implement strict security measures. Communications become more coded, meetings more carefully planned, and new recruitment virtually stops.

Your caution proves wise when the FBI begins investigating "subversive activities" in the camps. Several people are questioned, but the coded communications protect most of the network. Those few who are arrested refuse to reveal names, taking punishment to protect others.

The network survives but operates at reduced capacity. However, this security-focused approach builds trust and loyalty that lasts beyond the war. Many of your contacts remain connected, forming the foundation for post-war civil rights organizing.

When camp resistance leader James Omura is arrested for sedition, your secure network helps coordinate legal support and publicity for his case. The connections you built in secret become the backbone of public advocacy.

Breaking the Silence

You decide that the time for secrecy is ending. Working with journalists and civil rights lawyers, you coordinate a massive public exposure of camp conditions. Photographs, testimonies, and documented evidence flow through your network to the outside world.

The coordinated revelation creates a media storm. Newspapers across the country publish stories about unconstitutional conditions, family separations, and the economic devastation caused by forced removal. Your network's documentation provides irrefutable evidence.

The public exposure helps shift opinion about the incarceration. While it doesn't immediately end the camps, it creates political pressure that leads to earlier releases and better conditions for those still detained.

More importantly, your documentation becomes crucial evidence for future reparations movements. The careful records kept by your network provide the legal foundation for the 1988 Civil Liberties Act.

The Price of Resistance

The FBI discovers your network through an intercepted letter. Within days, coordinated raids across multiple camps round up dozens of your contacts. You're placed in solitary confinement, labeled a "dangerous subversive."

During interrogation, you're offered a deal: reveal the names of your contacts in exchange for better treatment. You refuse. Other network members also remain silent, even under pressure. The bonds you built prove stronger than fear.

Months pass in isolation. But gradually, you realize that even exposure hasn't completely destroyed what you built. Guards whisper news that sympathetic lawyers are filing appeals. New networks are forming to support those punished for resistance.

Your sacrifice inspires others. The network may be broken, but the idea of resistance spreads. Years later, former incarcerees tell you that your example gave them courage to keep fighting for justice.

From Underground to Mainstream

As the camps close, your network transitions into one of the most effective civil rights organizations of the post-war era. The communication skills and trust relationships built underground become powerful tools for above-ground organizing.

Former network members spread across the country, carrying organizing principles and contact lists. The Chinese American contacts you cultivated during your underground work prove especially valuable-- they've been fighting exclusion laws for decades and share strategies and resources.

By 1965, when the Immigration and Nationality Act finally repeals Asian exclusion laws, your network has evolved into a national Asian American civil rights coalition. The underground resistance of 1943 has become the foundation for political power in 1965.

Looking back, you realize that building trust under the worst circumstances created bonds that survived decades. Your network didn't just resist incarceration-- it transformed American civil rights organizing.

The Informant

Someone within your network has been feeding information to the authorities. Three of your most trusted contacts are arrested on the same night, clearly the result of inside knowledge. Trust-- the foundation of your entire operation-- has been shattered.

You implement emergency protocols, isolating different cells of the network while you investigate. The hunt for the informant becomes a painful process of questioning friendships and examining motives.

Eventually, you discover the betrayer: a man whose family was threatened with transfer to the harshest camp unless he cooperated. When confronted, he breaks down: "They said they would send my wife to a camp in the desert. My children wouldn't survive it."

The revelation forces a terrible choice: punish someone who acted from love and fear, or forgive and try to rebuild. How you handle this betrayal will define not just the network, but the kind of leader-- and person-- you became.

The Long Fight Continues

Your wartime network becomes the foundation for decades of civil rights work. The secure communication methods you developed prove invaluable for coordinating with other minority rights organizations during the 1950s and 60s.

You work closely with the NAACP, sharing strategies and supporting each other's legal challenges. Your experience with government persecution helps you understand the broader patterns of racial oppression in America.

In 1965, when President Johnson signs the Immigration and Nationality Act, several of your old network contacts are in the audience. The law that finally ends Asian exclusion is partly the result of organizing networks that began in barbed wire camps.

One of your former contacts becomes a federal judge. Another is elected to Congress. A third builds a successful law firm specializing in civil rights cases. The underground resistance has grown into institutional power.

Breaking Through the Silence

Your coordinated media campaign creates the first widespread public awareness of conditions inside the incarceration camps. Photographs smuggled out through your network appear in major newspapers. Radio programs feature interviews with former incarcerees.

The public reaction is mixed but significant. While some Americans defend the incarceration as "necessary for security," others are shocked by the evidence of constitutional violations and poor conditions.

Religious groups begin organizing relief efforts. College students stage protests. Labor unions pass resolutions condemning the incarceration. Your network's documentation provides credible evidence that makes denial impossible.

Most importantly, the media attention reaches family members of incarcerees who had been kept in the dark. Your network helps reunite families and rebuild communities torn apart by forced removal.

Evidence for Justice

Your network's careful documentation becomes the foundation for legal challenges that span decades. Every letter saved, every photograph smuggled out, every testimony recorded becomes evidence in the fight for justice.

Civil rights lawyers use your documentation to file wartime challenges to Executive Order 9066. While most are unsuccessful during the war, they establish legal precedents and preserve evidence for future cases.

In the 1980s, when Congress begins considering reparations, your network's documentation proves crucial. Lawmakers can no longer claim ignorance or minimize the scope of injustice-- the evidence is overwhelming and irrefutable.

When President Reagan signs the Civil Liberties Act in 1988, authorizing reparations for Japanese American incarcerees, you're in the audience. The law exists partly because you and your network refused to let history be forgotten or distorted.

Alone with History

In the isolation of solitary confinement, you have time to think about resistance, sacrifice, and the meaning of citizenship. The authorities hoped to break your spirit, but solitude becomes a space for deeper understanding.

You think about Frederick Douglass, who wrote that "where justice is denied, where poverty is enforced... neither persons nor property will be safe." Your resistance was not rebellion-- it was patriotism in its truest form.

Months pass. Guards occasionally bring news: Germany has surrendered. Atomic bombs have been dropped on Japan. The war is ending. But your war-- the fight for constitutional rights-- continues.

When you're finally released from solitary, other incarcerees treat you with quiet respect. Your sacrifice has meaning. The network may be broken, but the idea of resistance spreads. Years later, former incarcerees tell you that your example gave them courage to keep fighting for justice.

Seeds of Resistance

Your example of resistance inspires others long after the camps close. Former incarcerees carry your story with them, sharing it with their children and grandchildren. The idea that resistance is possible-- even under the worst circumstances-- becomes part of community memory.

In the 1960s, young Asian American activists cite your story as inspiration for their own organizing. The civil rights movement, the anti-war movement, and the emerging Asian American movement all benefit from the example you set during the dark years.

College students in the Third World Liberation Front strikes of 1968 carry copies of letters from your network. They understand that resistance has deep roots, that their struggle connects to earlier fights for justice.

By the 1970s, your story has become legend-- a reminder that ordinary people can do extraordinary things when they choose courage over comfort, resistance over compliance.

The Harder Path

You choose forgiveness, recognizing that the real enemy is the system that forced impossible choices, not the man who made them. The informant weeps when you tell him: "They used your love against you. That doesn't make you evil-- it makes them evil."

Rebuilding the network after betrayal proves more difficult than building it the first time. Some refuse to work with the former informant. Others admire your choice to forgive. The network survives, but changed-- perhaps stronger for having wrestled with the hardest questions of loyalty and humanity.

Years later, the man who betrayed you becomes one of your most devoted allies in post-war civil rights work. His guilt transforms into determined advocacy. Sometimes forgiveness creates the most committed fighters for justice.

Your choice to forgive becomes part of your leadership legacy. People say you understood that the system tried to corrupt everyone-- victims, perpetrators, and bystanders alike. True resistance meant refusing to let it corrupt your humanity.

The Price of Betrayal

You decide that some betrayals cannot be forgiven-- that the network's security requires consequences for treachery. The informant is exiled from the community, his betrayal made known to prevent future collaboration with authorities.

Your decision splits the network. Some support your choice, arguing that resistance requires discipline. Others feel that punishment under these circumstances is cruel-- that everyone is a victim of the system.

The network survives but never fully recovers its pre-betrayal strength. However, it gains something else: a reputation for uncompromising principles. People know that joining your network means accepting responsibility for protecting others, regardless of personal cost.

Years later, you sometimes wonder if you chose justice or vengeance. The informant dies alone, his family never fully accepted back into the community. Your choice shaped not just the network, but the kind of leader-- and person-- you became.

From Resistance to Recognition

Your wartime network has made you a recognized leader in the civil rights movement. You're invited to speak at universities, testify before Congress, and participate in strategy sessions with other civil rights leaders.

When Martin Luther King Jr. organizes the March on Washington in 1963, you're among the Asian American leaders who help coordinate participation. Your experience building underground networks proves invaluable for logistical planning.

You use your platform to connect different struggles for justice. Your speeches often begin: "I learned about resistance in barbed wire camps, but I learned that resistance must continue long after the wire is cut."

By 1970, you've helped establish several Asian American civil rights organizations and mentored a new generation of activists. Your journey from underground organizer to national leader shows how resistance can transform both individuals and society.

Power and Its Responsibilities

Your network has achieved something remarkable: institutional power. Former underground organizers now hold positions as judges, legislators, university administrators, and civil rights lawyers. The question becomes: how do you use this power responsibly?

You work to ensure that gaining access doesn't mean losing edge. Your network maintains its commitment to grassroots organizing even as some members move into establishment roles. The lunch meetings now happen in government offices, but the agenda remains focused on justice.

When the reparations movement gains momentum in the 1980s, your network's institutional connections prove crucial. Having sympathetic voices in positions of authority helps navigate the complex political process required to pass the Civil Liberties Act.

You often remind younger activists that institutions can be tools for justice, but only if they're wielded by people who remember where they came from and why they sought power in the first place.

Putting Families Back Together

Your network's media work has an unexpected consequence: it helps families separated by the incarceration find each other. Letters pour in from relatives searching for loved ones, and your communication system becomes a reunification service.

You coordinate with Red Cross workers and religious organizations to track down family members scattered across different camps or lost in the chaos of forced removal. Each successful reunion feels like a small victory against the dehumanization of incarceration.

The work is heartbreaking and hopeful in equal measure. You help a grandmother find grandchildren she thought were dead. You connect siblings separated for three years. You facilitate the reunion of couples who married just before being sent to different camps.

This family reunification work becomes a model for post-war refugee resettlement efforts. Your experience coordinating across vast distances with limited resources proves valuable as America grapples with displaced persons from around the world.

The Long Arc of Justice

You're 86 years old, sitting in the audience as President Reagan signs the Civil Liberties Act. Around you are dozens of other former incarcerees, many of whom were part of your wartime network. The ceremony feels both triumphant and bittersweet-- so many who should be here are gone.

The President's words echo in the chamber: "The legislation that I am about to sign provides for a restitution payment to each of the 60,000 surviving Japanese Americans of the 120,000 who were relocated or detained."

As applause fills the room, you think about the long path from your first coded letter in 1943 to this moment. The documentation your network preserved, the testimonies you helped coordinate, the evidence you risked everything to protect-- it all led here.

After the ceremony, reporters ask about your role in the reparations movement. You simply say: "We never stopped believing that America could live up to its ideals. Today, it finally did."

Passing the Torch

Young Asian American activists seek you out during the Third World Liberation Front strikes at UC Berkeley and San Francisco State. They want to hear firsthand about resistance strategies, about building networks under surveillance, about maintaining hope during dark times.

You attend their meetings, sharing stories from the camps and lessons learned through decades of organizing. One young activist asks: "How did you keep going when everything seemed hopeless?" You reply: "We remembered that our resistance wasn't just for ourselves-- it was for people we would never meet."

The students adapt your underground communication techniques for their own organizing. Coded messages, secure meeting protocols, and network security practices developed in incarceration camps find new life in student organizing against the Vietnam War and for ethnic studies programs.

Watching these young people fight for their vision of America, you realize that resistance truly does echo across generations. The network you built in barbed wire has become part of the DNA of Asian American activism.

The Strength of Mercy

Your choice to forgive the informant becomes a defining characteristic of your leadership style. You become known as someone who can see the humanity in opponents, who understands that most people act from fear rather than malice.

This approach proves powerful in civil rights work. When negotiating with government officials, you focus on shared values rather than assigning blame. When working with other minority groups, you emphasize common experiences of exclusion rather than competing for victim status.

Religious leaders seek your counsel on reconciliation. Labor organizers ask you to mediate disputes. Your reputation for fair dealing opens doors that remain closed to more combative activists.

Critics sometimes call you naive, but results speak louder than rhetoric. The forgiveness you learned in the camps becomes a tool for building coalitions that span racial, religious, and class lines.

The Price of Principles

Your decision to exile the informant establishes you as a leader who values principles over comfort. Other activists know that working with you means accepting high standards and serious consequences for betrayal.

This uncompromising approach attracts dedicated followers but also creates enemies. Some see you as rigid, unforgiving, unable to understand human weakness. Others admire your clarity and consistency.

In civil rights negotiations, your reputation for inflexibility sometimes works in your favor-- people know you won't accept hollow promises or cosmetic changes. Government officials and corporate leaders take your demands seriously because they know you won't settle for less.

The cost is personal isolation. Fewer people seek your friendship, though many respect your leadership. You sometimes wonder if the price of unwavering principles is too high, but you can't imagine leading any other way.

Building for the Future

You focus your energy on creating institutions that will outlast you: scholarships for Asian American students, legal defense funds for civil rights cases, archives that preserve the history of incarceration and resistance.

The Asian American Civil Rights Foundation becomes your flagship project. Funded partly by reparations payments and managed by veterans of your wartime network, it provides legal support, educational programs, and historical preservation.

You insist that the foundation serve all Asian Americans, not just Japanese Americans. "Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere," you often quote, channeling Dr. King's words. Chinese Americans facing immigration restrictions, Korean Americans dealing with hate crimes, Vietnamese refugees seeking services-- all find support.

By 1990, the foundation has helped win dozens of legal victories, educated thousands of students, and preserved hundreds of oral histories. Your network hasn't just survived-- it has become institutionalized as a force for justice.

Making History Come Full Circle

In your 70s, you become one of the key leaders in the campaign for Japanese American reparations. Your institutional connections from decades of network building prove crucial in navigating Congressional politics.

Former network members now serve as federal judges, congressional staffers, and civil rights lawyers. The underground communication skills you developed are put to use coordinating a complex legislative campaign across multiple states.

You testify before Congress, your voice still strong at 85: "I am here not for myself, but for those who cannot speak-- those who died in the camps, those who never recovered from the trauma, those who believed America had forgotten them."

When the Civil Liberties Act passes in 1988, you're among the first to receive reparations payments. You immediately donate yours to the Asian American Civil Rights Foundation, saying: "This money belongs to the future, not the past."

From Incarceration to Liberation

Your experience with family reunification during the camps makes you a natural advocate for Vietnamese refugees fleeing the fall of Saigon. You understand the trauma of displacement, the challenge of rebuilding in a new country, the importance of maintaining family connections.

Working with Catholic Charities and other refugee resettlement agencies, you help establish programs that go beyond basic services. Your networks provide cultural orientation, job placement, and advocacy for fair treatment.

The parallels between Japanese American incarceration and Vietnamese refugee experiences are painful but instructive. Both groups faced suspicion, both were seen as foreign threats, both had to prove their loyalty to America.

Your refugee work becomes a model for helping other displaced populations: Cambodians, Laotians, later immigrants from Central America and Somalia. The communication networks you built in the camps become blueprints for coordinating international relief efforts.

The Long Road to Recovery

Your network becomes a support system for former incarcerees dealing with trauma, shame, and loss. Many Japanese Americans never spoke about their camp experiences, carrying the burden in silence for decades.

You organize support groups, informal gatherings where people can finally tell their stories without judgment. The network that once smuggled coded messages now carries testimonies of pain, resilience, and survival.

Working with mental health professionals, you help develop culturally appropriate therapy approaches. Traditional talk therapy doesn't work for everyone-- some heal through community service, others through artistic expression, still others through political activism.

The healing work extends to families. Children of incarcerees, who grew up with parents who couldn't discuss their experiences, finally begin to understand the silences and sorrows that shaped their households.

Beyond Compensation

The reparations victory represents more than money-- it's an official acknowledgment that the government can be wrong, that injustice can be recognized and addressed, that democracy can self-correct.

You spend your final years speaking to students about the lessons of reparations. "It's not about the money," you tell them. "It's about the precedent. It's about establishing that America can face its mistakes and try to make them right."

The Civil Liberties Act becomes a model for other reparations movements: African Americans seeking redress for slavery, Native Americans demanding land restoration, immigrants challenging discriminatory policies. Your network's documentation methods are studied and adapted.

As you age, you see young activists carrying forward the work. They face new challenges-- Muslim Americans after 9/11, immigrant families facing separation, refugees from new conflicts-- but they use strategies and principles your network developed decades earlier.

The Power of Quiet Dignity

After your release from solitary confinement, you choose a different path: leading through service rather than speeches, example rather than exhortation. Your sacrifice in the camps gives you moral authority that doesn't require demonstration.

You work behind the scenes, connecting people and resources rather than seeking spotlight. When young activists need mentoring, they seek you out. When community members face personal crises, they trust your counsel.

Your leadership style emphasizes listening over talking, building over breaking, healing over fighting. This approach attracts different followers-- people who value substance over style, long-term change over immediate gratification.

By the 1970s, you're recognized as an elder statesman of the civil rights movement. Your opinion carries weight precisely because you rarely offer it publicly. When you do speak, people listen.

Passing Down Wisdom

Your mentoring becomes your most important work. Young Asian American activists, civil rights lawyers, community organizers-- they all seek your guidance. You teach them not just tactics, but principles: how to build trust, how to maintain security, how to persist through setbacks.

Your protégés go on to lead major organizations, win landmark legal cases, and establish new institutions. Many say that your most important lesson was showing them how to balance idealism with pragmatism, how to fight for justice without losing their humanity.

You establish a formal mentorship program through the Asian American Civil Rights Foundation, pairing experienced activists with newcomers. The program becomes a model for other movements, showing how knowledge and experience can be systematically transferred between generations.

By 1990, your mentees include congressional representatives, federal judges, university presidents, and Nobel Prize winners. The network you built in the camps has spawned a generation of leaders who shape America's future.

Healing Old Wounds

Your forgiveness-centered approach leads to groundbreaking reconciliation work. You facilitate dialogues between Japanese American incarcerees and the children of camp guards, between immigrant communities and long-time residents, between victims of discrimination and those who perpetrated it.

These conversations are painful but necessary. A former guard breaks down describing the shame he's carried for decades. A camp administrator's daughter apologizes for her father's actions. Slowly, carefully, understanding begins to replace resentment.

Your reconciliation model is adopted by other communities: Native Americans and descendants of settlers, African Americans and descendants of enslavers, immigrants and nativists. The process you developed in dealing with the camp informant becomes a template for healing historical traumas.

Religious leaders invite you to speak about forgiveness. Psychologists study your methods for resolving intergenerational conflict. Your work shows that reconciliation doesn't mean forgetting-- it means remembering in a way that heals rather than harms.

Leadership's Burden

Your uncompromising stance creates respect but also distance. People admire your integrity but find it intimidating. Social invitations are rare; casual friendships are difficult when others feel constantly judged against impossibly high standards.

You find solace in the work itself. Late nights spent reviewing legal briefs, long meetings with other activists, strategic planning sessions-- these become your social life. The cause fills the spaces where personal relationships might have flourished.

Occasionally, you wonder what you've sacrificed for your principles. Watching other leaders laugh easily with colleagues, seeing them enjoy the fellowship that comes with shared struggle, you feel the weight of the walls you've built around yourself.

But when young activists seek your counsel, when hard-won victories validate your approach, when history vindicates your unwavering stance, you find meaning in the loneliness. Leadership sometimes requires standing apart, even from those who follow you.

Building to Last

The Asian American Civil Rights Foundation becomes your life's work. Starting with $50,000 in donations and three volunteers, it grows into a multi-million dollar organization with offices in six cities and a staff of over 100.

The foundation's legal defense fund wins crucial court cases: challenging discriminatory hiring practices, defending immigrant rights, securing educational access for non-English speakers. Each victory builds precedent for future battles.

Your scholarship program sends hundreds of Asian American students to college and graduate school. Many become the lawyers, doctors, teachers, and activists who continue the work. The investment in education pays dividends across generations.

The foundation's oral history project preserves thousands of testimonies from immigrants, refugees, and their descendants. These stories become the foundation for academic research, museum exhibitions, and educational curricula that ensure the experiences are never forgotten.

Universal Human Rights

Your refugee work expands internationally. You consult with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, help design resettlement programs in multiple countries, and work with international human rights organizations to address forced displacement worldwide.

Your experience with the camps provides crucial insights into the psychology of persecution and resilience. You help develop protocols for interviewing traumatized refugees, design community support systems that preserve cultural identity while facilitating integration.

Speaking at international conferences, you often begin: "I learned about human dignity in America's concentration camps. I learned that walls and barbed wire cannot contain the human spirit, but they can teach us what freedom really means."

Your work contributes to the development of international human rights law. The documentation methods your network used in the camps become standard practices for human rights organizations worldwide.

Healing the Family Tree

Your work with Japanese American families reveals deep intergenerational trauma. Parents who never spoke about the camps. Children who grew up with unexplained silences and unprocessed grief. Grandchildren who inherit anxiety and shame without understanding their source.

You develop family therapy approaches that honor both individual healing and cultural values. Group sessions bring together multiple generations, creating safe spaces for stories that have been buried for decades.

The breakthrough moments are profound: a grandfather finally telling his grandson about the humiliation of losing his business, a grandmother sharing her fears about speaking Japanese in public, adult children understanding why their parents were so focused on assimilation and success.

This work becomes a model for other communities dealing with historical trauma. Native American families, Holocaust survivors, descendants of enslaved people-- all adapt your methods for their own healing processes.

A Life of Resistance

In your final years, journalists and historians seek you out for interviews. They want to understand how a young man building underground networks in barbed wire camps became an elder statesman of the civil rights movement.

You tell them: "Resistance isn't a single moment of heroism. It's a lifetime of small choices to stand with the oppressed rather than the oppressor, to speak truth rather than comfort, to build rather than tear down."

Looking back, you see the threads that connect your story: the trust built in the camps, the networks that survived decades, the principles that never wavered, the hope that outlasted every setback.

Your final speech, delivered at the opening of the Japanese American National Museum, concludes: "We built our networks in the worst of times because we believed in the best of possibilities. That is what America is-- not what it has been, but what it could become."

The Wisdom of Age

As one of the last surviving leaders of wartime resistance, you become a living link to history. Presidents seek your counsel on civil rights issues. Supreme Court justices invite you to speak about constitutional law. Your voice carries the authority of someone who has seen democracy's greatest failures and greatest triumphs.

You use this platform carefully, speaking only when you have something important to say. Your rare public statements carry enormous weight because people know you choose your words deliberately.

Young activists still seek you out, but now they come not just for tactical advice but for perspective. They want to understand how to maintain hope across decades, how to build movements that outlast individual leaders, how to create change that endures.

Your final public appearance is at the dedication of the National World War II Memorial. Standing before the crowd, you represent not just Japanese American incarcerees, but all who have fought for justice within American democracy.